A survey into the food waste habits of communities in Wellington, Tauranga and Dunedin has shown surprising results.

The Love Food Hate Waste Pilot Intervention Project followed the food waste habits of 75 participants, providing an intervention group with educational resources to find out if Love Food Hate Waste resources would be effective in reducing the amount of food wasted by participants.

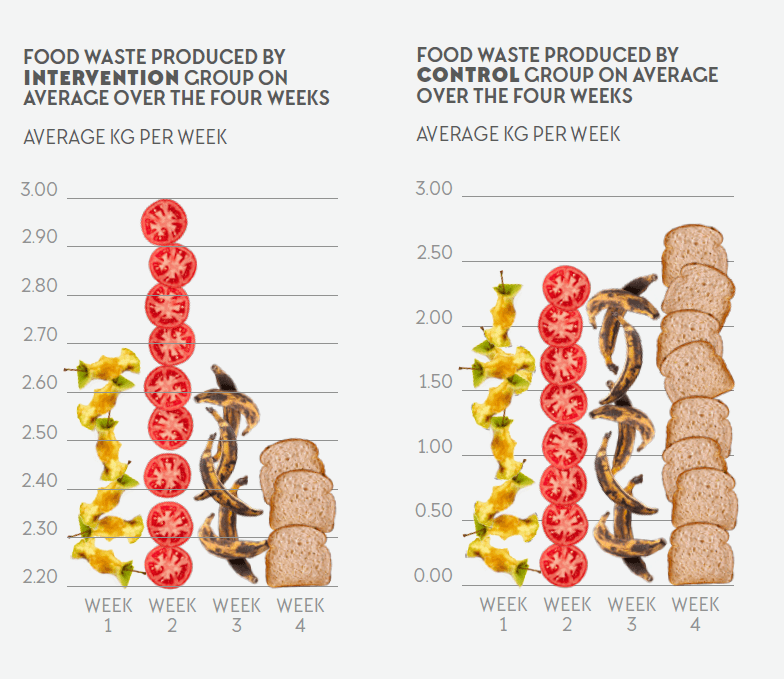

Results showed that the resources helped the intervention group who reduced its food waste overall by 7% over four weeks. In contrast, the control group, which was not provided with resources but was asked to measure their food waste each week, increased its food waste by 22% over a four-week period.

The majority of intervention participants found magnetic meal planners and the “quick tips” posters to be quite useful or very useful in reducing food waste.

Emma, an intervention group participant said the project helped her to reuse food, rather than wasting it.

“We have reduced our food waste volume-wise but most importantly the proportion of waste that could have been reused has drastically reduced. We are eating more fresh produce (and buying less) and our leftovers selection going to the freezer now means we have more options for nights when we don't feel motivated to cook.”

Dunedin City Council’s Catherine Gledhill said the council took part in the survey because Dunedin has a high student population who fit into the “high food waster” category.

“Dunedin City Council is moving to kerbside food waste collection next year but we’re still focused on reducing food waste in the home.

“The intervention did have some impact which is really pleasing to see. For us, it backs up our ongoing support for the Love Food Hate Waste campaign. We share the Love Food Hate Waste message as part of any food waste initiative that we’re involved with and we share it with community groups who may want to impart those resources to their members.”

What is the Pilot Intervention Programme?

WasteMINZ, which coordinates Love Food Hate Waste, knew from previous studies that certain groups were the highest food wasters:

- Those aged 16 to 24 years in the household responsible or jointly responsible for food shopping and preparation (i.e., flatting).

- Large households i.e., those with four or more people living in them.

- Households with children aged 15 years and under.

- Households with a high annual income (in 2018 this was considered to be over $100,000 but due to high inflation impacting on housing, transport and foods costs it could now be considered to be $150,000 per annum or more)

We wanted to find out if interventions, such as educational resources, would reduce the amount that these groups wasted.

The Pilot Intervention Programme was developed with the help of an expert who provided guidance on who to target and what to do. Three local councils were involved – Wellington, Tauranga and Dunedin City Councils.

What was involved in the study?

The participants were divided into two groups: a control group and an intervention group.

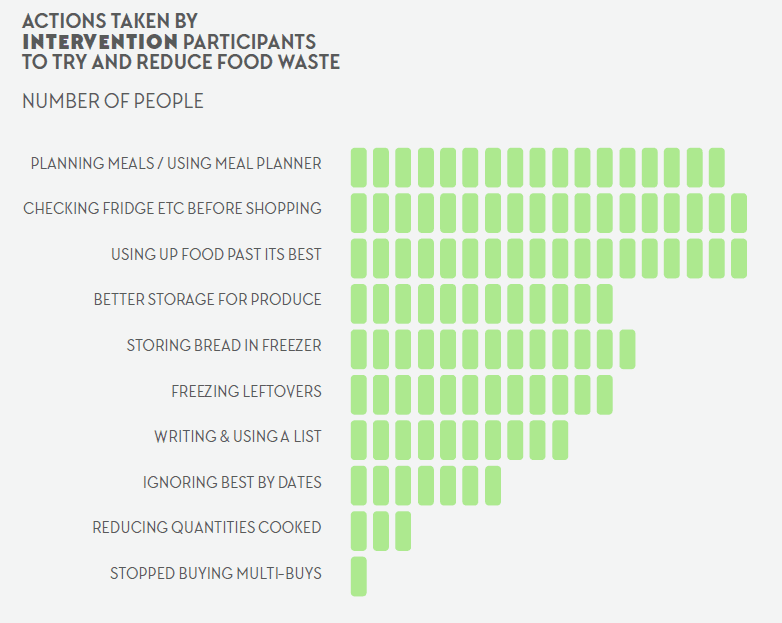

Both groups were asked to measure their food waste and answer a short survey each week for four weeks, but the intervention group was provided with education – including tips about meal planning, what to do with leftover food and how to reduce food waste overall.

At the end of the four weeks, we collated and analysed the survey results from both groups. Our key findings are below.

Who took part?

There were initially 76 participants but one person did not complete the whole four weeks, which meant 75 participants’ food waste was included in the final analysis.

Behaviours and motivations – key findings

At the start of the project, we asked a series of questions that prompted the participants to identify behaviours and motivations related to topics such as food, shopping, storage, cooking, disposal methods and more.

The top ways of getting rid of food waste were:

- Home compost (35%)

- Rubbish bin (28%)

63% of participants were the main food shoppers, while 29% share the task.

How did participants reduce food waste before shopping?

- 12% always use a meal plan, and 9% always write their shopping list based on a meal plan (lowest).

- The majority of participants agree or strongly agree that when food shopping they always or often think carefully about how much they will use (highest).

Food management at home – key highlights:

Results of the Intervention Project

For the intervention groups, food waste went from an average of 2.7kg per week down to 2.51kg (with a peak of 2.99 in week two). Overall there was a 7% decrease in food waste for the intervention groups. The peak in week two is unexplained: potentially participants took longer to start measuring their food waste so week one included fewer days than it should have.

For the control groups, food waste went from an average of 2.32kg per week up to 2.82kg. Overall there was a 22% increase in food waste over the four weeks for the control groups. It is unclear why food waste increased for the control group rather than staying the same. However, 95% of the control group participants said they had previously taken action to try and reduce their food waste but during the four weeks of the study only 29% of the control group said they had taken action to try and reduce their food waste.

Actions taken by intervention participants

Most useful resources

Intervention participants were supplied with a variety of resources such as New World/LFHW weekly meal planners, magnetic whiteboard meal planners, quick tips and other posters, videos, online resources, and eat me first stickers. In order of usefulness:

- 80% of respondents found the magnetic meal planners to be quite useful or very useful

- 74% of respondents found the “quick tips” and other posters to be quite useful or very useful

- 38% of respondents found that some or all of the online LFHW resources (Such as the A-Z storage guide and the recipe database) had helped them, while a further 32% said they had given them lots of ideas to put into action in the future.

What’s next from here?

The participants will be sent a follow up survey before the end of the year to see if any of the behaviours they adopted during the four-week project have “stuck”.

This study had a very small sample so is not conclusive, but it did show some promising results. Feedback from the participating councils have highlighted that the study could be modified slightly, as outlined below:

- Have no control group

- Baseline data could be collected for two weeks before the participants are given the resources. However, having a six-week project could increase the dropout rate of participants.

- Ask respondents if they prefer online or printed resources

- Have fewer resources

- Tailor the project so that participants received a link to resources at the time they are getting ready to do their food shopping for the week